Latest Headlines

Amupitan’s Thankless Job

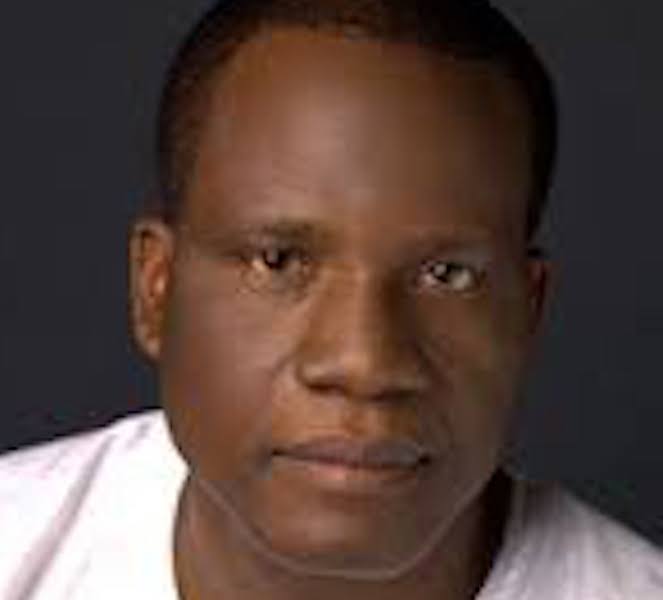

Kayode Komolafe

President Muhhamadu Buhari did a great thing on June 12, 2018, by recognising Bashorun Moshood Abiola as president-elect and Ambassador Babagana Kingibe as Vice President-elect. This was 25 years after Abiola won a presidential election as the candidate of the old Social Democratic Party (SDP) with Kingibe as his running mate. Buhari conferred on Abiola posthumously the highest national honour of the Grand Commander of the Order of Federal Republic (GCFR) and on Kingibe the second highest honour of the Grand Commander of the Order of the Niger (GCON).

The election was held on June 12, 1993. So Buhari declared June 12 as the Democracy Day, a change from May 29 earlier proclaimed by the administration of President Olusegun Obasanjo as the Democracy Day. Obasanjo was first sworn in as president on May 29, 1999.

Doubtless, the occasion was essentially a validation and celebration of the June 12, 1993, election.

But there was not even an applause for Professor Humphrey Nwosu, the chairman of the National Electoral Commission (NEC) that conducted the election deemed to be the “freest and fairest” in many quarters. So, Nwosu died an unsung hero in the June 12 story. During the week of his funeral earlier this year, a motion to immortalise his memory was defeated on the floor of the Senate. There was a stiff opposition to the motion by senators who regarded Nwosu as “anti-June12” and “lacking in courage of conviction.” The suggestion that the headquarters of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) be named after Nwosu was also ignored. All this happened 17 years after Nwosu had documented his travails as the head of the electoral commission that conducted the much-applauded June 12 election in a book entitled “Laying the Foundation for Nigeria’s Democracy: My Account of the June12, 1993 Election and its Annulment.” He narrates in the book his ordeal as he struggled to defend the sanctity of the election. Yet, instead of praising Nwosu, his memory unjustifiably received condemnation. It was, however, immensely redemptive for Nwosu that on June 12 this year President Bola Tinubu conferred a posthumous award of the Commander of the Order (CON) of the Niger (CON) on the political scientist.

The fate of Nwosu is, perhaps, typical of chief electoral officers in Nigeria’s political history. In this political culture the efforts of the umpire are hardly appreciated. All that is remembered is what went wrong and little or nothing is said about the positive things done by the umpire. At the end of the tenure of the umpire all that remains is a tale of woes. This should, perhaps, not be surprising in a political clime in which election is taken by some politicians as war and not a festival of democracy.

Sometimes you wonder if anyone would like to take up the thankless job of INEC’s chairman in the future.

Such has been the trend since the appointment in 1964 of the first indigenous chairman of the electoral commission, Mr. Eyo Ita Esua, a teacher and trade unionist, who was in charge during the crisis-ridden 1964/1965 elections. His tenure ended at the end of the First republic in 1966. Before Esua’s tenure, a colonial officer, Ronald Edward Wraith, was appointed as the chairman of electoral commission in 1958. Wraith was in the saddle to organise the 1959 election of the government that was in place at independence in 1960.

Between Esua and the new chairman of the electoral commission, Professor Joash Amupitan, Nigeria has had 11 substantive chairmen of electoral commisssion and a lady in an acting cpacity. The following are the names of the chief electoral officers and their respective tenures: Michael Ani (1976 – 1979), Victor Ovie-Whiskey (1980 – 1983), Eme Awa (1987–1989), Humphrey Nwosu (1989 – 1993), Okon Edet Uya (1993–1993), Sumner Dagogo-Jack (1994 – 1998), Ehraim Akpata (1998– January 2000), Abel Guobadia (2000–May 2005), Maurice Iwu (June 2005 – April 2010), Attahiru Jega (June 2010 – June 2015), Amina Bala Zakari (Acting, June – November 2015) and Mahmood Yakubu ( November 2015- October 2025).

None of the chairmen listed in the foregoing had a controversy-free tenure. Electoral disputes especially at the presidential elevel defined most of the tenures. Virtually every chairman ended being demonised and harrassed.

Indeed, some chairmen of the electoral commission had spectacular moments. For instance, in the build-up towards the 1983 presidential election the chairman of the Federal Electoral Commission (FEDECO), Justice Ovie-Whiskey, was accused of receiving a bribe of one million naira from a politician. In denying the unproven allegation the retired judge reportedly said that he would “faint” if he sighted a million naira cash! Talking about his own experience in office as chairman of NEC, Professor Awa, an eminent political scientist, famously said: ”if I open my mouth, Nigeria will burn”! Such is the turmoil that sometimes defined the tenures of chairmen of the electoral commission.

That is why the exceptionality of the Jonathan moment bears remarking any time the electoral institution is being discussed. President Goodluck Jonathan made history by accepting the verdict announced by Jega as the chairman of INEC in 2015. In fact, Jonathan congratulated Buhari before the collation of the votes were completed. Hence there was no dispute by the candidate.

Yet Professor Jega has hardly received an appaluse from politicians for the conduct of an election in which a sitting president conceded defeat as a candidate. Before the election, politicians and interest groups had expressed fears and levied allegations against Jega. In fact, spokesmen of some interest groups supporting a candidate alleged on television that they had “minutes of the meeting” in which Jega allegedly planned with another political party to rig the 2015 election. None of those allegations has been proved 10 years after Jega left office. In the eyes of the losers of elections conducted by INEC under Jega’s leadership, all the technical innovation introduced during his tenure amounted to little or nothing.

Yakubu’s story is far from being a departure from the pattern of total condemnation. The bitterness against him in some quarters still lingers. He has been accused of promising to deploy technology to enhance speed and tranparency in the process but failed because of what INEC described as “technical glitches” His critics are unrelenting even after his exit from the seat. Yet, those who declare Yakubu’s tenure a “total failure” while they are in the mood of hypercriticism would in another moment celebrate remarkable things that happened during the 2023 elections. The standard criticism was that INEC was a tool in the hands of the governmet in power. But the same INEC declared the results of the party in power losing in states where it would be expected to be dominant. Another outcome of the 2023 election is that candidates of eight political parties won elections into the National Assembly namely the All Progressives Party (APC), Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), Labour Party (LP), New Nigeria Peoples Party (NPP), All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA), African Democratic Congress (ADC), Social Democratic Party (SDP) and Young Progressives Party (YPP). And, of course, candidates of two opposition parties – PDP and LP- won as governors. All these categories of elections were conducted by the same Yakubu’s INEC that was declared a “total failure” by those displeased with the result of the presidential election.

To be sure, the legitimacy of criticisms of INEC is not in dispute because of its pivotal task. The outcome of INE’s work determines who would hold positions of political leadership at various levels. In fact pointing out the errors and weakneses of INEC is necessary to strengthen it as an institution of democracy.

It is also fact of life that as a human exercise the conduct of elections cannot be perfect.

It is, therefore, important to have a sense of balance in the assesment of those who are given the task of umpires. While errors or infractions must be fought, the integrity of INEC should be respected as a central institution of Nigeria’s liberal democracy. Unduly demonising virtually every head of the electoral would rather erode public confidence in INEC rather than building it as an institution.

Amupitan is taking off on an optimistic note by saying that elections should be decided at the polling booth and not in the courtroom. That’s a goal that is worth pursuing during his tenure. He certainly needs the critical support of stakeholders to succeed in choosing that path.